Operation Storm from a Diplomatic Perspective:

Without a Return Visa

Each of the 145 witness testimonies from the trial of Gotovina, Čermak, and Markač could serve as the basis for a separate text. The online exhibition format made it possible for parts of around twenty testimonies to be interwoven throughout existing narratives. However, one appearance before the Hague Tribunal stands out for its comprehensiveness, relevance, and analytical depth. It is the testimony of Peter Galbraith, the first United States Ambassador to the Republic of Croatia, who was appointed to that position in June 1992 and remained until 1998. He was, therefore, in office while Operation Storm swept through "Krajina".

Before testifying in the Gotovina et al. case, Galbraith had given evidence at the trial of the former President of the "Republic of Serbian Krajina", Milan Martić. Speaking about Martić's decision to reject negotiations over the peace plan known as the Z-4 Plan, he said: "I considered him a man of very limited ability, very limited intelligence, and far below the level required by the interests of Krajina and the Krajina Serbs. I don't think he was acting in the interests of the people in Krajina, but rather that he was primarily interested in his own position. Faced with what the whole world could see – that Croatian forces would erase the Krajina Serbs – when it was clear to everyone that Milošević would not support him, nor would the Bosnian Serbs, he still refused to negotiate. He still rejected an agreement that would not only have allowed people to remain but would have granted them a high degree of autonomy. (...) So not only did he reject the plan, but he refused even to discuss it. In that sense, Martić was Franjo Tuđman's best friend and ally because he gave Tuđman the excuse he needed to ensure that Serbs would no longer be present in the Krajina region."

The former US ambassador met with the Croatian president on 1 August 1995, the day after the Brijuni meeting and three days before the launch of Operation Storm. Galbraith told Tuđman at the time that the United States was not prepared to give a green light for the offensive, but that if a military operation did go ahead, "Serbian civilians must be protected and that any repetition of the crimes that occurred in the Medak Pocket in 1993 would have very serious consequences for US-Croatian relations." He said he issued that warning because he knew that Tuđman "viewed Serbs as a threat and wanted a homogeneous, ethnically pure Croatia."

The fears of the American administration soon came true – numerous crimes were committed against Serbian civilians during and after Operation Storm, while relations between Croatia and the United States deteriorated.

Describing the course of the operation from a US diplomatic perspective, Galbraith said that the shelling of towns and villages in "Krajina" was not necessarily seen as a violation of international humanitarian law. Embassy staff, including military attachés, described the shelling as "relatively short, not overly destructive," and occurring within the framework of an operation aimed at militarily seizing territory. Ambassador Galbraith added that, in his view, Operation Storm did not constitute ethnic cleansing because most of the population had left before Croatian forces entered.

He did say, however, that he believed Croatia "would have carried out ethnic cleansing if the Serbs had stayed," a conclusion he reached based on events that marked the immediate post-Operation Storm period in the liberated area.

Already in the first days following Operation Storm, systematic looting and destruction of abandoned Serbian property began. It seemed, he said, as though everything was being done on orders, or at the very least, with the tacit approval of the authorities. He described how one employee of the US Embassy in Croatia, while surveying the area on the outskirts of Knin, saw houses burning. Nearby, he spotted members of the Croatian Army and complained to them, saying: "The house is on fire. Are you going to do something about it?" And then, Galbraith said, "he realised that those were the very people who had set the house on fire."

For Galbraith, the motives behind the destruction of Serbian property were obvious: "Once you burn their house, seize their property, and kill their livestock, there is no way for anyone to return and actually live there."

In addition to property destruction, the US Embassy had information about the systematic killing of several hundred Serbian civilians who had remained in "Krajina".

All of these crimes, he believed, were not occurring spontaneously, but rather to realise Tuđman's idea "of a homogeneous Croatia."

The final straw in the deterioration of US-Croatian relations was the Croatian authorities' decision to confiscate all abandoned Serbian property if the owners did not request its return within thirty days. Galbraith explained that under US pressure, the deadline was first extended to ninety days, and then in December 1995 – by which time the damage was almost impossible to undo – it was abolished altogether.

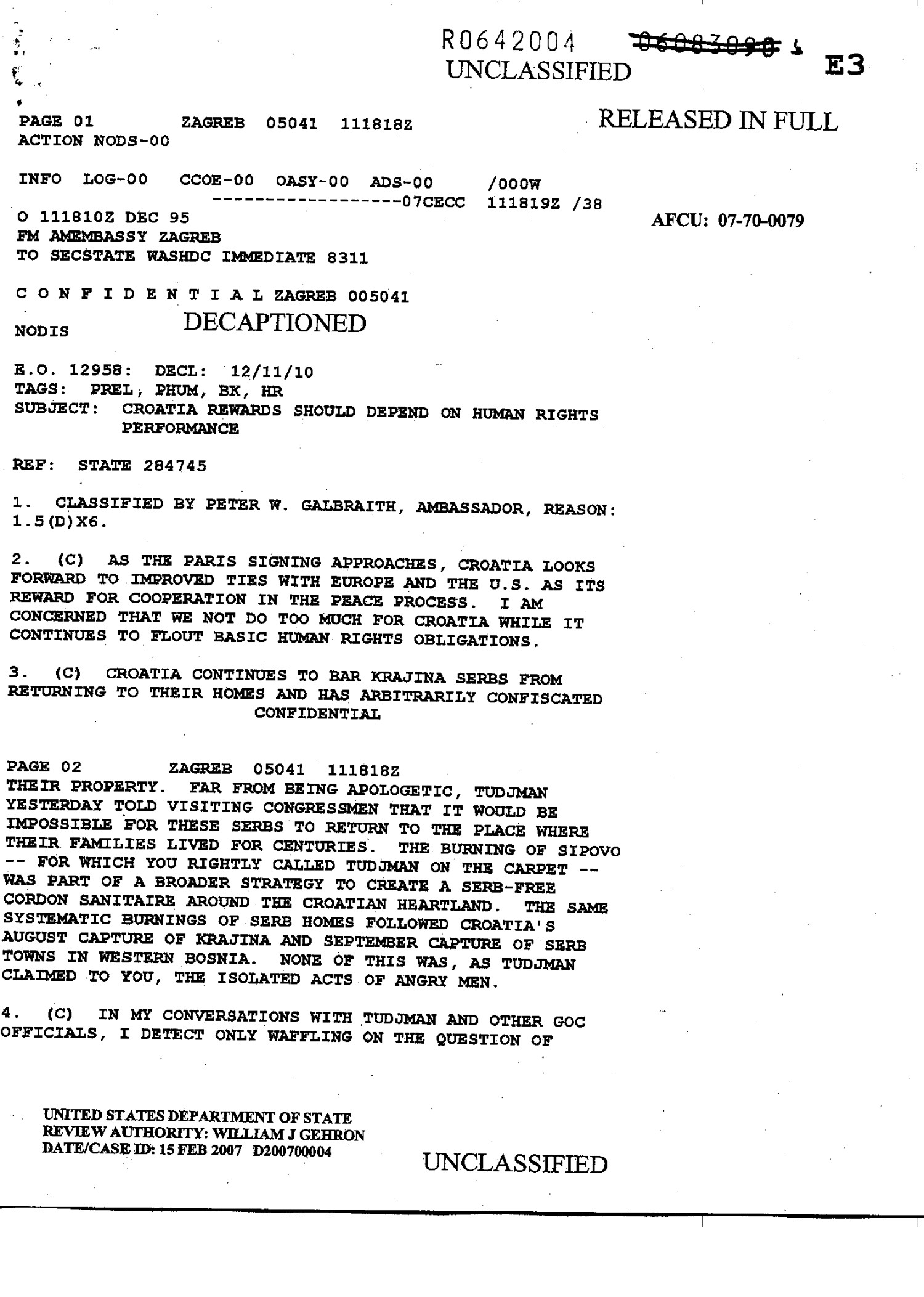

The state of US-Croatian relations at the time is clearly reflected in a diplomatic cable dated 11 December 1995, in which Galbraith informed the US Secretary of State that Croatia "scoffs at its basic human rights obligations" and proposed that Croatia's path to NATO and the European Union be made conditional on enabling the return of Serbs, adhering to international human rights standards, and cooperating with the Hague Tribunal.

Relations only began to improve after the death of Franjo Tuđman and the rise to power of more liberal politicians, who were more willing to cooperate with Western partners and wanted to change policies regarding the return of displaced Serbs.