Victims of Operation Storm:

We Have Been Roaming the World Ever Since

After the shelling of Knin, Gračac, Obrovac and other towns in areas under the control of rebel Serbs began on the morning of 4 August 1995, a large number of Serbian civilians started to leave the area alongside the army. Most of them managed to cross into Bosnia and Herzegovina or Serbia, although they were attacked in various ways along their route to exile. Those who fared worst, however, were the people who could not leave, or who believed the promises of the Croatian authorities that nothing would happen to them if they chose to stay.

Some of those who survived these events later testified before the Hague Tribunal.

Marija Večerina, a Serb woman from the village of Muškovac in the municipality of Obrovac, fled "Krajina" on 5 August with her daughters Mira (b. 1970) and Branka (b. 1971), her son Stevo (b. 1974), and a group of other villagers. They were heading towards the town of Srb, as suggested in a leaflet they had found while moving through the Velebit mountains. A close reading of the Brijuni meeting transcript shows that considerable discussion took place there about dropping leaflets with instructions for Serbian civilians on the quickest route to leave Croatia.

Near the village of Očestovo, in the municipality of Knin at the time, their red Lada came under fire. Marija and her son were wounded, she in the arm, he in the leg. A large number of Croatian soldiers then surrounded the car. All of its occupants were taken captive and brought to a nearby house where a group of detained Serbs was already being held. The following day, Marija's wounded son Stevo and four other men were taken from the house on the pretext that they were being taken to hospital.

All five of those men were killed. Marija and her daughters escaped to Serbia. It was not until 2003 that they learned Stevo Večerina's body had been found at the cemetery in Knin. That same year, Marija's daughters Mira and Branka moved to Canada.

Mirko Ognjenović was in his native village of Kakanj, in the municipality of Kistanje, when the war broke out, and when Operation Storm began. He believed the Croatian government's assurance that civilians could remain safely. "I stayed because I was listening to the radio — 'Those who are not guilty, don't need to go anywhere' — Tuđman's statement broadcast on the radio," he said in his testimony before the court. That call corresponds to the fact of "supposedly guaranteeing human rights" that Franjo Tuđman announced at the Brijuni meeting five days before Operation Storm began.

In the days that followed, Ognjenović, his relatives, and neighbours in Kakanj saw their human rights violated daily and in every imaginable way. Their homes were looted and burned, livestock killed, and they were subjected to constant insults and threats from Croatian soldiers. Finally, on 18 August 1995, a group of armed men opened fire on a group of Kakanj villagers. Mirko Ognjenović (b. 1921) and his neighbour Radoslav Ognjenović (b. 1908) were wounded, while two other neighbours, Uroš Ognjenović (b. 1928) and Uroš Šarić (b. 1920), were killed.

Mile Đurić from the village of Plavno, near Knin, testified about an incident that took place on 6 August 1995, when members of the Croatian armed forces killed his father, Sava Đurić (b. 1942). Croatian soldiers first set fire to the house and workshop on the Đurić family homestead. Hidden in a neighbour's yard, Mile saw the soldiers throw his father into the burning workshop. Sava Đurić was burned alive in that building. Fleeing from Croatian soldiers who were shooting at him, Mile reached Serbia only after full fifteen days. He was reunited with the rest of his family there much later.

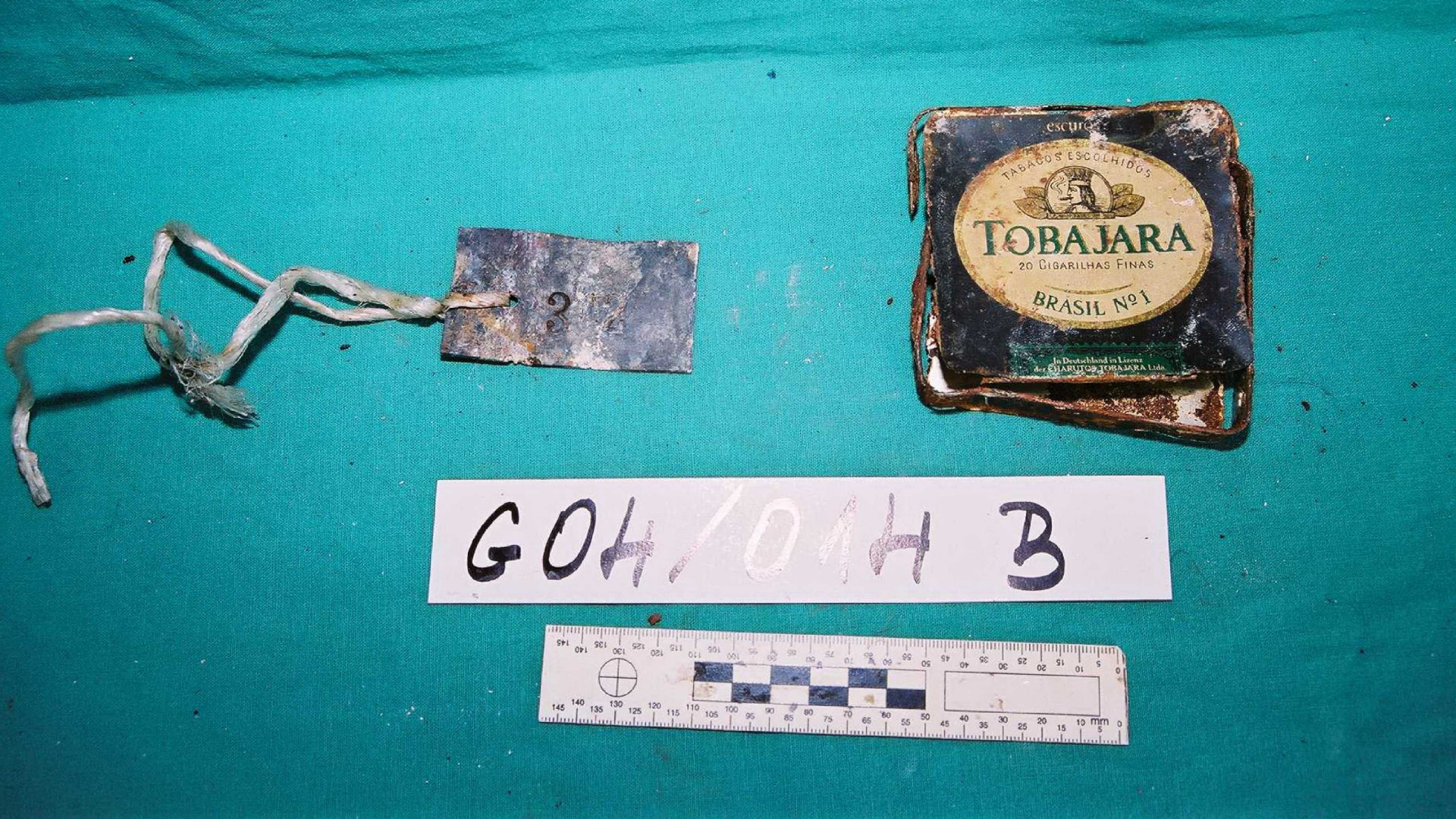

Mile Sovilj from Gračac went to his native village of Kijani on 4 August 1995 to organise his extended family's departure from "Krajina". He managed to persuade everyone except his father, Vlade Sovilj (b. 1931), who refused to leave, saying that every hour on the radio, Croatian President Franjo Tuđman was urging Serbs not to abandon their homes and assuring them that nothing would happen to them. Not long after, by 12 August at the latest, Vlade Sovilj was killed in Kijani along with thirteen other mostly elderly Serbian civilians. The perpetrators remain unknown. Years later, Mile Sovilj recognised his father's exhumed, almost entirely burned body by a small patch of unburned clothing and a metal cigarette case he had bought him two years earlier, which his father always carried with him.

Since August 1995 Mile Sovilj has been living in Serbia.

Sava Mirković from the village of Polača near Knin also left his home on 4 August 1995 and set off with his wife and two daughters for Serbia. His mother, Đurđija Mirković (b. 1925), refused to go with them. "Why would anyone want to kill me, I'm just an old woman," she said, explaining her decision. Eight days later, Croatian soldiers killed her, cursing her Serb mother, as eyewitnesses recounted.

Sava Mirković remained living in Serbia with his family.

These five brief examples speak to the fate of more than 600 killed and around 200,000 displaced Serbs from "Krajina" during and after Operation Storm. The ethnic composition of that part of the Republic of Croatia was irreversibly changed, entire families were destroyed, and every individual life after Operation Storm is a story without a happy ending.